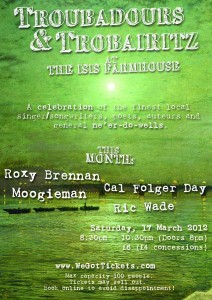

Some of us singer-songwriter types like to liken ourselves to troubadours. Some of us even call ourselves troubadours. This Saturday Moogieman, along with local performers Ric Wade and Roxy Brennan, and the enchanting chanteuse from New York Cal Folger Day will be taking on this designation (or in the case of the female performers, ‘trobairitz’) for James Bell’s monthly night at the Isis Tavern, by Iffley Lock.

But who were the troubadours, and what about the more obscure trobairitz? Since the gig was first advertised I’ve been surprised by how many people were unfamiliar with the term ‘troubadour’, though most were able to guess that trobairitz was the female version. To put it simply, the troubadours were singer-songwriters of the high medieval period (11th to 14th centuries) – so the link with today’s performers is straightforward enough.

James Bell explains: ‘The idea came from a fringe event that I ran for the Oxford Folk Festival a few years back. I was putting on Catweazle people and I wanted a name that kind of illustrated how they’re part of a singer-songwriter tradition that goes back … well … centuries. It must be short and easy to remember, I thought.’

The name has certainly caught people’s attention. However, delving deeper into the history of the troubadours things become more complicated. When I first heard the term, as a school kid with an interest in (okay, obsession with) medieval history, the term troubadour was synonymous with ‘wandering minstrel’ and probably came up in connection with the story of Blondel and his role in ‘rescuing’ Richard I of England, aka the ‘Lionheart’.

The story goes that Richard the Lionheart was captured on his way back from the Third Crusade and held for ransom in a secret location. His faithful retainer Blondel (the name refers to his flowing blond locks) travelled around Europe, from castle to castle, playing a song known only to himself and the king until, at long last, he heard the king respond with the second verse, thus identifying his whereabouts. Depending on the version of the story, Blondel then either helped the king to escape or reported his position back to his friends who were able to raise the ransom.

The tale is almost entirely fictional. Richard I was imprisoned, but it was no secret where he was held – there would clearly be no point in holding someone to ransom and then making it impossible for their followers to find out who to pay the money to. Blondel was, loosely speaking, a troubadour from France who fought in the Fourth and Albigensian crusades, but the troubadours were not wandering minstrels. They usually occupied a settled position at court and were mainly of noble birth, sometimes very high ranking. Almost certainly he never met Richard the Lionheart and owed him no allegiance, and certainly wouldn’t have traipsed around Europe looking for him (not least because the king didn’t need to be found).

The troubadours were generally very keen to distinguish themselves from travelling minstrels of low birth, called joglars or jongleurs, who didn’t write their own songs and also provided other forms of entertainment (the more restricted English term ‘juggler’ derives from ‘joglar’).

The troubadours originated in 11th century Occitania, a region roughly comprising the southern half of France (also taking in Monaco and parts of Italy) and initially came exclusively from the nobility. The earliest well-documented troubadour was William (Guilhem) IX, Duke of Occitania (also known as Aquitaine) and Count of Poitou. He was the grandfather of Eleanor, wife of Henry II of England. Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the major female figures of the High Middle Ages, being immensely rich and powerful as well as being known for her learning and as a patron of the arts (including patronage of troubadours).

Later, troubadours spread to Italy, Spain and further field. Other forms such as the satirical political song developed, and some troubadours devoted themselves to writing political verse on behalf of the Guelph or Ghibelline factions (the broad division of the Papacy vs the Holy Roman Empire that played out across much of southern Europe, especially Italy, throughout this period.)

The trobairitz were much rarer. They were the first female composers of non-religious music and all the known ones were aristocratic and came from Occitania. There are thought to be far fewer trobairitz than troubadours and very little of their work survives. The confinement of trobairitz to southern France is probably due to the distinctively powerful position of Occitanian noblewomen compared to their contemporaries in the rest of Europe – in particular, their greater land ownership rights and the administrative responsibilities left to them by husbands and fathers who had departed for the crusades.

So can we claim to be modern-day troubadours and trobairitz? If artists can consider themselves to be latter-day Hellenes, knights, pirates, Victorian villains, punks or prophets then so long as we’re careful not to get into some kind of medieval re-enactment (apart from that being incredibly tedious the troubadours themselves certainly weren’t characterised by obsessive recreation of the past) then why not?

And there’s certainly more than a few similarities. We generally don’t play cover versions like the lowly joglars (and when we do these are well-considered homages or ironic pastiches of course). Sometimes we’re so up our own arses we like to think we have a nobility of taste and refinement, if not of blood. And we have a tendency to sing twee songs about unrequited love, just like the troubadours sang about courtly love (and in fact were partly responsible for inventing the whole modern notion of ‘love’). Essentially it’s music for people who aren’t getting any. Though, as with the troubadours, there are of course exceptions.

The Moogieman performance at the Isis will include a new piece, The Unfinished Song Of the Troubadour In Space, incorporating the verse structure of troubadour lyric poetry, and also a sestina, a unique poetic form believed to have been invented by the 12th century Provençal troubadour, Arnaut Daniel. More info in the next update.

Tags: Medieval history